Photo credit: Matt Austin

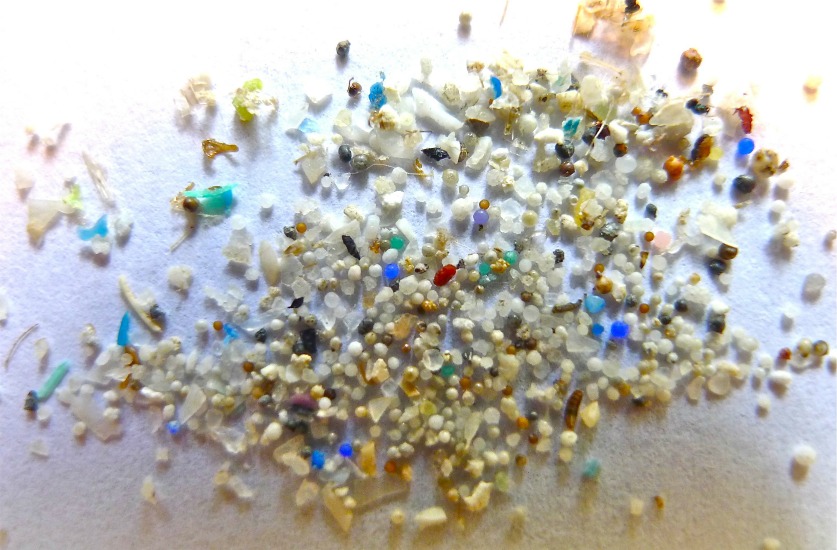

I’ve recently spent a lot of time in pursuit of face scrubs, the common end of the market variety that millions of consumers use to polish tired, stressed skin to remove blackheads and other impurities. You can get a face scrub for morning, noon and night; honestly they market them for different times of the day. The problem is these scrubs are by and large full of microbeads, a sub division of microplastics and the ocean is awash with them.

Yes, under our noses – and very often on our noses – the personal care industry has introduced an ‘innovative’ ingredient that makes passive pollution almost unavoidable. Yes, as soon as you buy an exfoliator, or toothpaste that can contain around 300,000 microbeads per tube and decide to use it, you’re unwittingly committing an act of eco-hooliganism.

How did this happen?

Well, actually, the use of microbeads in cosmetics was considered something of a breakthrough. Not only are they cheap, but they’re uniform and do a job (removing dead skin) really well. Previously, cosmetics employed natural bits of walnut husk or apricot kernel – and many alternatives still do. A lecturer in cosmetics talked me through some products recently and recalled seeing ‘natural’ exfolliants under the microscope and being horrified. ‘Pieces of walnut and apricot looked like tiny fragments of glass,’ she remembered. This was being rubbed enthusiastically on to skin in the quest for beauty but could actually damage the epidermis. In this context uniform, rounded tiny beads were a breakthrough.

But they weren’t such a boon for the world’s oceans. Because it transpires microbeads cannot be washed away. Too small to be captured by sewage works, they bob along and out to sea. But what happens to them then?

We feel like we know a lot about plastic waste in the oceans. The principal swirling vortex of plastic waste remains the Eastern Garbage Patch, the nickname of one of the planet’s five subtropical gyres. Today’s eco adventurers (a hipster job title if ever I saw one) flock to these parts to vlog and ‘raise awareness’ of the scourge of plastic waste. It’s often breath-taking stuff, a grim inventory of everyday disposable plastic items towed around by ocean currents.

Eco Adventurers and Ocean Plastics

But – at the risk of mixing my metaphors – this is just the tip of the iceberg. What I like about this part of the story is that the substantive, breakthrough research on plastic waste in the ocean has been conducted by a guy who has spent a large part of his scientific career out in all weathers in the Tamar Estuary, leading to the English Channel. It’s not glamorous and he does not vlog, in fact, Dr Richard Thompson of Plymouth University in the Southwest of the UK, is more reminiscent of a 1970s TV detective than an eco-adventurer. But while everyone else was going, ‘OMG look at all this plastic!’ he got on with doggedly crunching the numbers and wondered why there wasn’t a hell of a lot more.

In common with many connoisseurs of flotsam, Thompson’s office errs on the cluttered side. A prize exhibit is a ‘degradable’ plastic bag from a well known supermarket, one of a number of examples of plastic waste overflowing from the shelves. Other exhibits include coloured plastic bottles. Because the plastic has been dyed blue with a pigment the plastic is harder to recycle. Plastic that is not recycled is more likely to become ocean debris. The point of the bag was that it was made from a plastic that would fade away. Thompson’s point is that it has not. Only now is part of it beginning to flake. Plastic is notoriously persistent. What Thompson realised was that we were failing to account for plastics that breaks down into microplastics.

In Lost At Sea?, a landmark study of 2004, Thompson and his team were able to identify microscopic pieces of plastic that had been scooped up with plankton samples in the North Atlantic starting in the 1960s and to coin the term ‘microplastics’ (now commonly used) to describe tiny pieces of plastic under 5mm in diameter and previously ignored. At last a proportion of that missing plastic had been accounted for.

Thompson’s detective work continued. Last year he published a new study that showed that far from bobbing around on the surface of the 5 gyres, an abundance of microplastics were likely to have accumulated at the bottom of the sea. Seemingly buoyant particles sank as they weathered, were colonized by organisms or caught up in storms. In short he has uncovered another huge sink.

Thompson may dislike coloured plastic drinks bottles, but he reserves particular frustration with microbeads in cosmetic products. A short journey up the A38 to Exeter University and the laboratory of Dr Matt Cole was to show me why these are particularly worrying.

Photo credit: 5 Gyres

Matt Cole’s specific interest – some might say obsession – is in copepods, creatures that make up part of zoo plankton and therefore form an intergral part of the oceanic food chain. Under the microscope you can see these creatures hyperactively darting about which is absorbing enough. But then flick a switch and you can see in sharp relief the neon-dyed contents of their tiny stomachs: microbeads. Cole’s research has demonstrated how copepods can ingest microbeads instead of food. Without energy they fail to function properly. This is alarming.

So, here’s a rhetorical question:

Is an exfoliating face wash really worth affecting the basis of all oceanic life?

Some US states don’t think so. A law in Illinois and a bill in Maryland (microbeads have been identified in major watercourses in both) bans manufacture of products containing microbeads by the end of 2017 and would prohibit their sale in these states by the end of 2018. Some companies including Unilever, L’Oreal, Colgate-Palmolive and Johnson & Johnson say they are phasing out use of the beads. Procter & Gamble says it plans to remove microbeads from dental products by next year.

Unfortunately that still commits us to billions of legacy microbeads as all the remaining products are bought and used. And as we know from Thompson’s research, they might end up anywhere including Antarctic ice or as deep sea sediment. Hands up if you feel comfortable waiting for voluntary phase outs? As consumers we have to police ourselves. As ever, there’s an app for that http://get.beatthemicrobead.org (although I think it could do with logging a few more products) where you can scan the bar code on your phone and to check if it’s microbead-free before purchase. Look for polyethylene or similar in the ingredients list, however small the print, and give them a miss. Purge your bathroom cabinet of any products containing microbeads and send them to landfill. It’s hardly a utopian ending, but better than releasing them into the watercourse.

In the meantime you have to wonder what the sustainability departments at these major brands were up to. Why weren’t the formulations sense-checked with someone who could have looked at them from an ecological perspective. At that point my dream corporate conversation would’ve gone something like this: ‘listen formulation chemists, I’m no marine biologist but I don’t think filling products with tiny plastic beads is a good idea, after all they stand an above average chance of ending up in our life-sustaining water ways.’ Perhaps it’s due to the silo-ed way that sustainability teams operate within business that that did not happen. Whatever the reason why, the world’s biggest brands turned customers who just wanted to exfoliate into passive polluters.

Sources:

Global warming releases microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice; Obbard and Thompson et al

Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Worldwide: Sources and Sinks; Browne et al, 2011

Photo credit: van Franeker, J.A., et al., Save the North Sea’ Fulmar Study 2002-2004: a regional pilot project for the Fulmar-Litter-EcoQO in the OSPAR area, in Alterra-rapport 11622005, Alterra (available at www.zeevogelgroep.nl): Wageningen.

Any suggestions for natural, non-harmful exfoliants?