Approx: 2,000 words, 6-10 mins

What does Professor Newport mean by “deep work”?

“Deep work: Professional activities performed in a state of distraction-free concentration that push your cognitive capabilities to their limit. These efforts create new value, improve your skill, and are hard to replicate.”

By contrast, he defines lesser tasks as follows:

“Shallow work: Non-cognitively demanding, logistical-style tasks, often performed while distracted. These efforts tend to not create much new value in the world and are easy to replicate.”

Newport hypothesises that deep work is an increasingly rare ability. Therefore, it is increasingly valuable in our information/intellectual economy. I agree. Newport puts it thus:

“To remain valuable in our economy, you must master the art of quickly learning complicated things. This task requires deep work. If you don’t master this ability, you’re likely to fall behind.”

Remaining valuable

Learning new things (acquiring skills) is not strictly cerebral and abstract; it can of course be physical. But in either case, it requires what Anders Ericsson, a professor at Florida State University coined “deliberate practice”. Such practice is necessary to master demanding tasks, and is itself a form of deep working.

Why did I buy the book?

[Skip this section if you want – it’s not important!]

Several years ago, I spent 12 months in a calorically restricted state, dieting down to single-digit percent body fat as a quasi-self-experiment (having read Ancel Keys’ 1950, two-volume text, The Biology of Human Starvation). After a short time, I could rarely sleep much past 5:00am due to acute hunger, regardless of how late I went to bed or ate the previous night.

Routinely, I would wake at 4:00-4:30am, make a coffee, and go to my garage gym, go out for a run, read, or some combination thereof (I haven’t owned a TV for years, so watching something wasn’t an option). I mention this because several months into the diet, I recognised that the amount of reading I got through in the 3 or so hours before the rest of the world started e-mailing, calling, and becoming active on social media platforms was truly astounding. I could sometimes read an entire book before it was time to wake my wife with a coffee, before going to work.

So late last year, as I scrolled through Amazon’s list of suggested titles and came across DEEP WORK, something occurred to me: I had been doing deep work, and post-diet, now able to sleep until my 7:30am alarm actually went off, I had stopped. I wanted to get back to deep working (without dieting!), so for this reason, I simply had to buy the book.

Can I do deep work, at work?

Let me begin by saying that if left alone I am not easily distracted from a task. If I need to get something done I am relentless and ruthless in equal measure. However, like almost everyone in the workplace, and especially in management, I am often distracted by external provocations—as a company director I’m a walking, talking decision engine. This latter fact had me worried because, seven pages in, Newport announces that there is mounting scientific evidence that if you spend enough time in “a state of frenetic shallowness”, you can permanently reduce your ability to perform deep work. Distraction becomes debilitation. Permanently.

After reading another 50 pages or so, I was convinced of the need to batch my time for important projects, and hard, cognitive problems. I hit upon a formula within a few attempts at deep work that enables me to achieve an incredible level of productivity, as follows:

- At some point during the morning (before 11am), I decide what time of the afternoon I will work on important or hard problems.

- Before I begin deep work, I turn my office phone to DND, unplug the Ethernet cable from the back of my Mac, and lock my phone in the car.

- I make a cup of strong coffee, and grab a snack (OK, snacks!) to take to my desk.

- I then return to my office, shut the door, and work for up to 2 hours.

Radical increases in productivity

Presently, I am undertaking my second masters degree (MSc psychology). The suggested amount of time spent studying each week is around 16 hours, split between performing research and writing essays. I have discovered that in approximately three to four deep-work-hours i.e., one quarter or less the time it should take me, I can:

- Read, make notes on, and internalise the required reading material for the week.

- Research books and related journal articles to enhance my understanding.

- Draft, edit, and submit an essay of distinction grade.

Work Goals

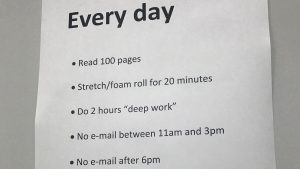

My every day to-do list stuck to my office wall.

By the time I had read the first half of the book, I printed out and stuck on my wall an A4 sheet of paper with my revised “Every Day” to-do list.

I quickly discovered these policies to be a nice balance of being available to colleagues and higher value clients, and being able to grind out some of my most important work, free of interruptions. I also find that adopting the deep work mind-set—and importantly, creating the environment for deep work by removing distraction—eliminates any form of procrastination; there’s nothing to do other than singularly focus on the task.

It seems to take me about 10-20 minutes to “go deep”, as Newport puts it, and once in the zone, I can maintain a ferocious concentration for around an hour. Interestingly, he asserts that the most practised individuals can perform deep work for a up to 4 hours a day, so I have a long way to go before my deliberate practice of deliberate practice maxes out. The possibility of increasing my productivity by 400% is exciting!

In the meantime, while I build my deep work capacity up to the four-hour mark, if a task requires concentration and undistracted effort for longer than I can manage in a single session, I batch my deep working over the course of several days. (No problem or task I have encountered thus far has taken more than 5-6 hours of deep work).

At first glance, a few hours a week doesn’t seem like a great deal of time to spend on what are, by definition, the hardest and most important problems I face. However, Newport offers a compelling argument to the contrary, “in many cases, contributions to an outcome are not evenly distributed”. In other words, it’s Pareto’s 80/20 principle.

Busyness vs Productivity

Another excellent observation in the book is that when people are not given explicit instructions as to what it means to be productive, they resort to being “busy”. As Newport puts it:

“Knowledge work is not an assembly line, and extracting value from information is an activity that’s often at odds with busyness, not supported by it.”

Strategies

The book also contains some rather aggressive strategies to help you work deeply. Here’s a couple that I used already (go me!), but have adapted since reading the book:

1 – Quit social media

Newport’s argument is persuasive. He summarises most social media interactions as, “I’ll pay attention to what you say, if you pay attention to what I say—regardless of its value”. Looking at our own company twitter account (@SuperFastSurvey), for instance, I can’t fault his assessment. Reflecting on this, I put out a tweet to the effect the account was no longer active—because we are too busy delivering for clients (to bother wasting everyone’s time with another picture of a newt we found on a development site). We also permanently deleted our company Facebook account, and so now only retain a presence on LinkedIn, which I do think offers value to the company. Even so, I limit my LinkedIn interactions to 10 minutes once every other day.

Dearest Follower. This account is no longer active. We’ve chosen to do this in order to concentrate on delivering for clients. Best, A-Team.

– Arbtech (@SuperFastSurvey) January 16, 2017

What does this mean for me? Well, I could hardly be described as a social media addict in the first place (I don’t have any social media apps installed on my phone, for example), but I am now certain that I don’t fall into the trap of allowing my mind to “bathe for hours in semiconscious and unstructured Web surfing”.

2 – Do less e-mail

Newport says “Do not reply to an e-mail [or any message] if any of the following applies:

- It’s too ambiguous.

- It’s not an interesting question or proposal.

- Nothing good happens if you respond and nothing bad happens if you don’t.”

This is great advice. I declared war on e-mail at our company in mid-2016, because the volume of e-mail traffic was getting out of hand. I won’t go into the detail here of how we tackled it (I’ll save that for another blog post), but it has certainly reduced the volume of e-mails I receive, especially internally, to a much more agreeable degree (<10 a day). However, once the overall volume had dropped, I felt obliged to read and respond to all of them. Not anymore! Most of the time these days I don’t respond to e-mails, and the rest of the time, I don’t even read them. It’s comforting to know that Newport’s view seems to align with mine; “the expectation that every message deserves a response is absurdly unproductive”.

Quantifying depth

One of the things I like about this book it that is outrageously practical. Newport, unlike many academics, doesn’t just tell you what not to do; he tells you precisely what to do, and how to work out whether your work is deep, or shallow.

I almost ran out of ink in my pen underlining sentences, scribbling notes, and circling entire paragraphs as I made my way through the book. One of the things that stood out most clearly (and is practical), was Newport’s method of reckoning the depth of your work:

“How long would it take (in months) to train a smart recent college graduate with no specialised training in the field to complete this task?”

The argument he makes is that if the aforementioned graduate would require many months of training to complete this single task, then you are “leveraging hard-won expertise”, and if the graduate could pick it up quite quickly, then you are not, and the work should be regarded as shallow.

He cites among many the example of Radika Nagpal, who recognised the need to budget her time for both deep and shallow work, by first working backwards from the maximum number of hours per week she was prepared to work (50). Reading this, I drew an immediate parallel with the way I structure my own working week. These days I only work Monday-Wednesday. This means I am forced to prioritise and delegate with brutal efficiency, or watch my whole world go to shit in fairly short order.

Concluding

Deep working isn’t about being an uncommunicative, anti-social hermit. It’s about quantifying the depth of your tasks, applying as many filters to shallow work as is practical, and intelligently batching your time to deal with what remains in order of importance.

It is a fantastic book in almost every respect. It’s one of those rare books that genuinely enhances your life, and the aim of this review is to share that. I strongly recommend reading it, along with the author’s blog.

If you have comments, I’d love to hear them.

-R.

References:

Newport, C. (2016). DEEP WORK: Rules for focused success in a distracted world. New York, NY: Grand Central Publishing.