Despite some progress being made on UK air pollution levels, certain pollutant readings are rising. Air pollution remains a major public health threat, potentially contributing to thousands of deaths nationwide and impacting wildlife.

According to the World Health Organization, polluted air is `the greatest environmental threat to health’ and a major cause of diseases such as strokes and heart attacks. As well as the threat to human health, exposure to air pollution damages the natural world too, harming plants, insects, birds, soils and ecosystems. And in many of the UK’s most polluted areas, the air we breathe is becoming a shared threat.

This article considers the current position for our health and for wildlife; it explains how air quality is tracked, shows which places and species are worst-affected and explores what’s being done – and what still needs to be done – to clean up the air for all living things.

What is air pollution and why does it still matter?

Air pollution, according to the Joint Nature Conservation Committee, the public body that advises government on nature conservation, is the presence (or introduction) of harmful substances in the atmosphere – gases and tiny particles – that can damage lungs, soils, plants, water, and food chains.

Key sources of air pollution include surface ozone (O₃), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), ammonia (NH₃) and sulphur dioxide (SO₂), emitted from coal burning: (SO₂) reacts with (NOₓ) and (NH₃) in the atmosphere to form particulate matter; there is strong evidence that this is a major source of damage to lungs. These pollutants come from many sources: road transport, heating and fuel burning, agriculture (especially ammonia from livestock and fertilisers), industrial processes, energy generation from power plants and wood burning.

According to Defra, at high levels nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide and ozone gases irritate lung airways, worsening symptoms for people exposed who suffer from lung diseases. Fine particles can travel into the lungs, causing inflammation, while carbon monoxide gas prevents blood from taking up oxygen, which badly affects people suffering from heart disease, leading to premature deaths.

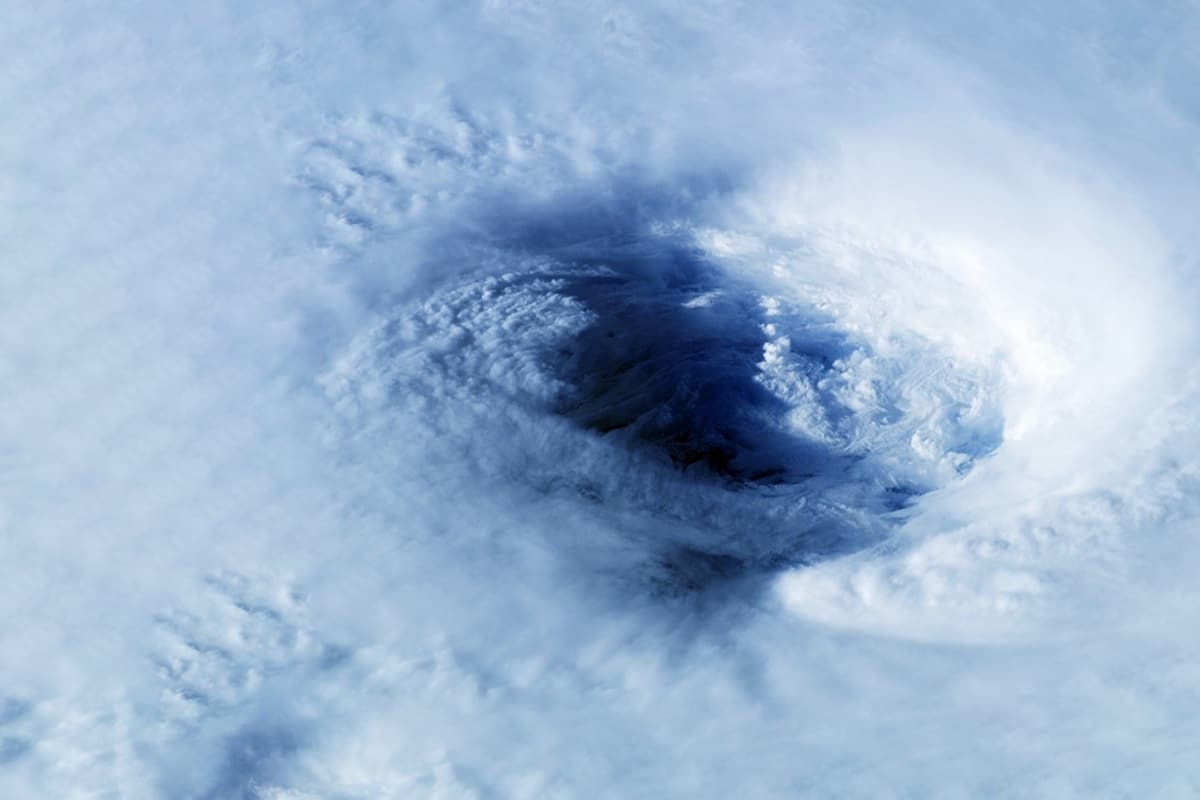

Globally, levels of air pollution can also be affected by wildfire smoke, volcanic eruptions, indoor air pollution, natural sources and building materials.

Some progress – but more needs to be done

In recent years the UK has made progress on reducing air pollution, partly due to clean-air zones in cities, but the problem remains. A nationwide analysis covering 500 monitoring sites found that NO₂ (a common traffic pollutant) and fine particulate matter (PM₂.₅) have fallen significantly over the past decade – by about 35% and 30% respectively.

However, a paper published in the journal of Environmental Science: Atmospheres found that while air quality in the UK has improved, there is a need for local and international cooperation to make progress on different types of air pollution. For example, ozone is worsening while other pollution is improving. Ozone, a secondary pollutant formed from the interaction of sunlight with NOₓ and other emissions, makes breathing for many humans and animals problematic.

According to the study, many places see dozens of days each year when pollutant levels exceed World Health Organization recommended limits.

Health impacts and unequal exposure to air pollutants

Air pollution in the UK remains a major public health threat. A recent report by the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) estimates that in 2025, air pollution may contribute to the equivalent of 30,000 deaths nationwide and cost the economy tens of billions annually through healthcare, lost productivity and diminished quality of life.

The report noted growing evidence that toxic air, even at low concentrations, affects nearly every organ in the human body and called for urgent action to reduce emissions from transport, heating (especially from burning fossil fuels such as natural gas) and agriculture, and to make clean air part of national health policy and climate strategy. Raising awareness of the health problems that human made air pollution causes is a priority.

Deprived areas may see higher levels of pollution

Air pollution guidance from the Office for Health Improvement & Disparities states that short-term exposure to air pollutants worsens asthma, bronchitis, other respiratory diseases and cardiovascular disease; long-term exposure increases risk of lung cancer, stroke, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other chronic conditions.

The burden of air pollution is not shared equally. People in deprived areas, especially near busy roads, cities or dense housing, tend to breathe more pollution and suffer more harm. For example, it may affect birth outcomes for pregnant women who may have low birth weight babies or their lung development or cognitive function may be impacted; older people are another sensitive group that is more susceptible to the harmful effects of ambient air pollution and its associated health impacts.

So, air pollution remains a public health crisis, and it especially impacts poorer communities and vulnerable people: air pollution affects children, the elderly and those with pre-existing health conditions, often resulting in ill health and reduced life expectancy.

Air pollution and nature

Air pollution doesn’t stop at affecting humans; it is a leading risk factor impacting ecosystems, habitats and wildlife, often in ways we rarely see. According to the Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC):

- Over a third of UK land area (approximately 91,000 km²) is sensitive to acidification (from pollutants like SO₂ and NOₓ).

- A similar area (approximately 94,000 km²) is vulnerable to nitrogen enrichment (from NOₓ and NH₃). Many areas are sensitive to both stressors.

When pollution exceeds so-called “critical loads” – thresholds above which significant harm is likely – eco-systems are at risk. That includes heathland, bogs, acid grassland, upland moors, ancient woodlands and other semi-natural habitats where the damage air pollution inflicts can be extreme.

So, what happens?

Loss of habitat for pollution-sensitive plants

Many plants and lichens that thrive on low-nutrient soils, including rare wildflowers, bog plants, heathland heathers and mosses, struggle when nitrogen “fertilises” the soil. Fast-growing nettles, grasses, and competitive species take over, shading out less vigorous species. Bryophytes and lichens that draw nutrients directly from the air are particularly vulnerable. The JNCC notes that sensitive lichens and mosses can decline dramatically under polluted conditions.

Chain-reaction effects across food webs

When habitat plants die back, so does insect life; when insect numbers fall, birds, bats and other insect-eaters lose their food source. Amphibians, small mammals and pollinators suffer declines and the broader ecosystem fragments.

Acidification and soil damage

According to the JNCC and the Environment Agency, transportation of sulphur and nitrogen compounds by wind or water (deposition) can acidify soils and water bodies, disrupting aquatic life, fungi and soil microorganisms, undermining ecosystem health and reducing resilience to other threats.

In effect, air pollution affects and undermines biodiversity, especially species adapted to clean air, nutrient-poor conditions, or sensitive ecological niches.

Pollution hotspots: where the problem is worst

No region is immune, but the damage is worst where sources of air pollution overlap with sensitive habitats or dense human populations. Big cities such as London, Birmingham, Manchester, and other industrial or high-traffic zones see higher concentrations of NOₓ, PM₂.₅, ammonia and other pollutants. Historic and ongoing industrial activity, high vehicle density, and domestic heating (gas boilers, open fires and wood burners) combine to produce a toxic mix of air pollution.

Recent mapping by Friends of the Earth identified that more than a quarter of England’s neighbourhoods are `nature pollution hotspots’ where air, water, light and chemical pollution exceed thresholds harmful to wildlife. Areas such as Salford, Worsley, Eccles, Battersea, Vauxhall, Chelsea and Fulham featured among the worst areas for increased levels of pollution.

In many of these places, urban areas or regions near major roads, vulnerable species face a double threat: habitat loss from development, plus chronic air and chemical pollution.

What’s being done to address air pollution: monitoring, regulation and clean-air zones

Awareness is rising and so is policy action. National emission reduction commitments include:

Monitoring stations and regulation

The UK government, through bodies such as Defra, the Environment Agency and the JNCC, maintains air quality monitoring networks tracking NO₂, PM, ozone, ammonia and deposition rates. Annual reports show where pollution exceeds critical thresholds for habitats. Local authorities often enforce Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) in hotspots where the damage air pollution causes is evident: this can trigger action on traffic, emissions and planning: air quality assessments may be required to improve air quality to protect public and environmental health.

Clean-Air Zones are starting to show results

One of the clearest policy wins is from cities introducing Clean Air Zones (CAZs) or low-emission zones. For example:

- In London, after the 2023 expansion of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) to the outer boroughs, new data shows a 27% drop in NO₂ and a 31% drop in PM₂.₅ across outer London, with air-quality monitoring sites at 99% compliance in 2024, a major milestone.

- In Birmingham, a 2023 study found that after CAZ enforcement, NO₂ fell by up to 7.3%, once weather and seasonal effects were accounted for.

Experts estimate that across England, exposure to particulate matter pollution (the most dangerous microscopic particles) has fallen by more than half between 2003 and 2023. These figures show that concerted action on reducing exposure to pollution – traffic controls, incentives for cleaner transport, regulatory enforcement – can bring real improvements, for people and for nature.

Could cleaning the air safeguard nature too?

This is possible if ecological concerns are woven into policy, planning and enforcement. It could happen by:

- Expanding green buffers: woodland belts, hedges along motorways and green corridors around cities can filter pollutants before they reach sensitive habitats, catch particulate matter, and absorb nitrogen deposition.

- Prioritising low-emission heating and cleaner vehicles: reducing domestic gas burners, limiting wood stoves, promoting electric vehicles and improving public transport will cuts NOₓ, PM₂.₅ and ammonia emissions at the source.

- Including the environment in air-quality legislation: current air standards tend to focus on human health issues, but frameworks like those proposed by the Clean Air Day campaign are pushing for additional targets and protections for habitats and species sensitive to nitrogen and acid deposition.

- Monitoring ecological impacts, not just public health indices: track lichens, mosses, specialist plants, soil chemistry, aquatic species and insect populations, especially in hotspot areas. This will help spot degradation before it becomes irreversible.

What still needs to be done

Despite progress, significant challenges remain in reducing exposure to air pollution:

- Areas outside major cities – towns, suburbs, and rural zones – still often exceed safe pollution levels, particularly for nitrogen when it is spread by the elements. Sensitive habitats remain under threat.

- Pollution sources are diversifying: while traffic emissions are falling, domestic heating (solid fuels), agriculture, and ground-level ozone (thanks to rising temperatures and climate change) are becoming more important.

- Many monitoring and regulatory frameworks remain focused on public health risks and reduced life expectancy, with less attention to habitat health. Without integrated policy (transport, climate, conservation), ecological damage will continue.

- More research and long-term ecological monitoring are needed to link air quality index data with wildlife and habitat outcomes so that recovery can be measured.

Good air quality is vital for human and environmental health

Polluted air doesn’t stop at city boundaries, it drifts across fields, seeps into soils and streams, affecting humans and entire ecosystems that need clean air to function.

While air pollution is a global burden, the UK is making progress, evidenced by clean-air zones reducing traffic emissions, particulate matter pollution and NO₂ falling in many towns, and growing public awareness. But as the recent RCP report warns, toxic air remains a major public health catastrophe – and an ecological timebomb.

By making clean air a priority for people, wildlife and the wider environment, we can rebuild habitats and landscapes under stress and help the biodiversity at risk. But that will require sustained political will, joined-up policy and public engagement.